Nu Nunuk du Tukon

AS SUNG BY LAJI SINGERS MELECIO ALASCO, ROSITA ALAVADO

Nu nunuk du tukon, minuhung as kadisi na,

ichapungpung diya am yaken u ñilawngan na.

Kapaytalamaran ava su avang di idaúd,

ta miyan du inayebngan na, ta miyan du inayebngan na.

Nu itañis ko am nu didiwen ko

ta nu taaw aya u suminbang diyaken,

nu maliliyak a pahung as maheheyet a riyes

u minahey niya, u minahey niya diyaken.

The Nunuk on the Hill

The nunuk tree on the hill grew tender leaves and shoots,

then suddenly its crown was broken and I was caught beneath.

Now I can no longer watch the boat in the deep sea

for I stand on the side that is hidden, on the side that is hidden.

I weep in my sorrow

for the vast ocean has made me an orphan,

the pounding sea breakers, the strong currents,

they told me of my fate, they told me this.

U Anak Nu Munamun

AS SUNG BY LAJI SINGER FILOMENA HUBALDE

Anu kadawudawung ku du tukun di Valungut

Dawri a dinungasungay u anak nu munamun,

Ahapen ku na siya nu masen a sahakeb,

Dahuran ku na siya du mahungtub a duyuy,

Udiyan ku na niya a payrakurakuhen

A di chu’a pavulsayi su madahmet a chirin

Du kahawahawa ku niya u kaichay nu anak nu munamun.

The Child of the Munamun

Each time I look down from the hill at Valungut

I see the child of the munamun swimming in the waves,

I will gather her in my finest net

and place her in the deep coconut shell,

to take her home and care for her as she grows.

I will not utter a single harsh word

and take great care not to hurt the feelings

of the child of the munamun.

Laji is the traditional oral poetry of the Ivatan people of Batanes. These poems are new translations into English of the traditional poetry, as sung by the elder singers, who deserve full credit for being the original culture-bearers of this indigenous art form. Both of these lajis were sung in my presence as I recorded the singers and spoke with them about their craft. They generously granted me permission to share their lajis with the broader public. These were first published in Manoa Journal (December 2024). Please visit our ongoing community-based project on documenting and preserving laji at ivatanlaji.com.

Tanaga du Ivatan (Asa, Dadwa, Tatdu, Apat)

Tanaga is a traditional Filipino form of poetry. Each poem is composed of four lines, seven syllables per line, with various end-rhyme patterns. This is an excerpt from a series, titled simply Asa, Dadwa, Tatdu, Apat (One, Two, Three, Four), that uses Ivatan poetic language in the Tanaga form. Originally published in Manoa Journal, December 2024.

Tanaga du Ivatan: Asa

Masalawsaw sicharaw

Malatyat ‘changuriyaw,

Navuya mu u hañit?

Nadngey mu u valichit?

The day is full of wind

As a new dawn arrives,

Have you seen the brightening sky?

Have you heard the valichit sing?

Tanaga du Ivatan: Dadwa

Sumavusavung da na

U dadwa ka bayakbak,

Nu minaydak a chidat

Asa yatus vituhen.

The two bayakbak trees

are flowering:

a lightning bolt flashes,

a hundred bright stars.

Daybreak

Stepping into the smoke

that climbs the mountainside

carrying in its jaws the memory of fire

we vanish

stars flicker where

the sky’s blue dome

catches the smoldering mast

then emerge cloaked in silver ash

the sun’s rays lancing our throats into beads of flame

as we chant the world

into daybreak and dreams.

We found signs in the entrails of wild boars

as our holy women read the slaughter

that darkened the tips of their fingers red

and manacled their wrists in scripture

we chose to live even though

we knew enough of what was to come

or at least what we would become

in order to witness their arrival.

Let me tell you how it begins—

our children run from the shoreline

chased by the last trace of starlight in the sky

my daughter turns to me

cupping a spear of moonlight in her small palm

samurang

our footsteps pursued by echoes

as we leave the shallow mouths of coral

empty in our wake.

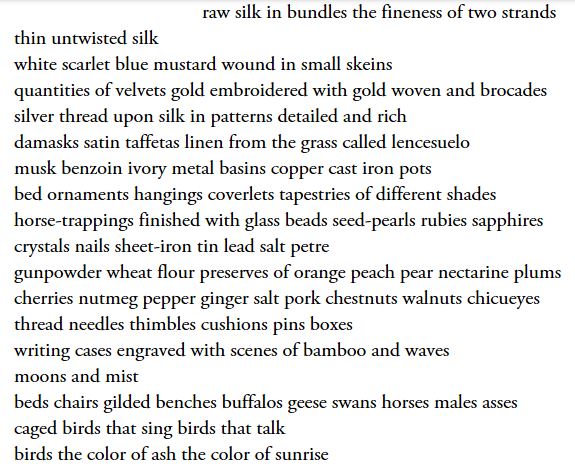

From yndio arxipelago (UP Press, 2025); art by Jay Pee Portez, from “Harvest”

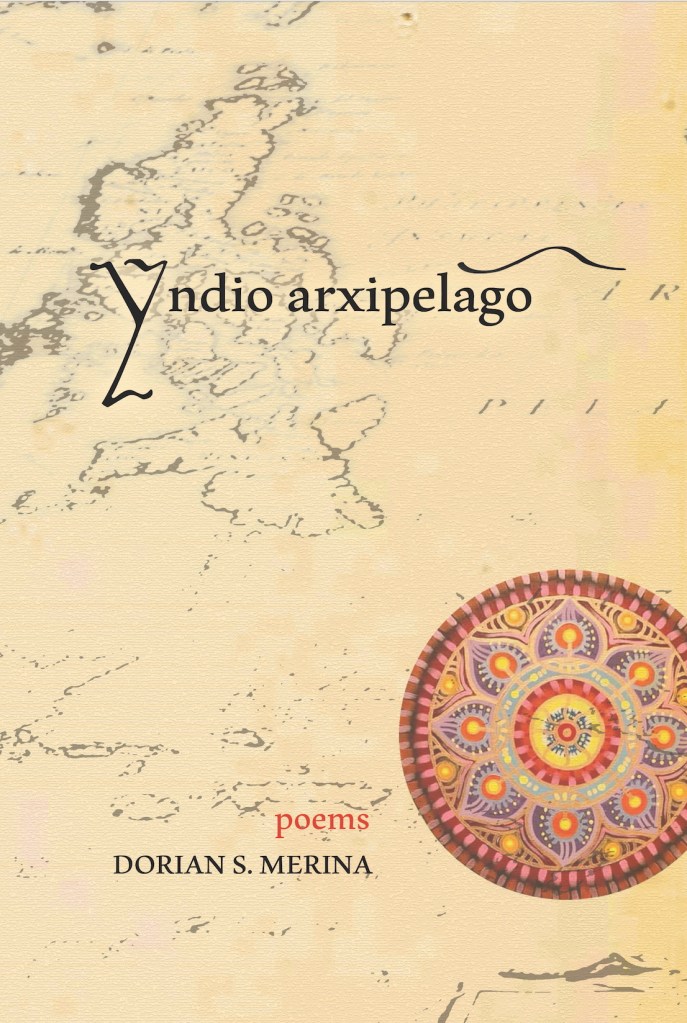

New Book of Poetry: yndio arxipelago

“A wondrous, fierce braiding of history, authority, and rebellious art. Merina’s poetic voice summons a necessary dignity for oppressed peoples of the past, bringing this balm of a book to our haunted present.”

—Laurel Flores Fantauzzo, author of The First Impulse

Out now from the University of the Philippines Press!

“In this luminous collection of poems, Dorian Merina invites us to sift through the colonial archives to discover who we were before conquest. With each line, he draws us into a journey not toward certainty but toward the unsettling truths buried in silence and omission.”

—SHEILA S. CORONEL, co-founder of the Philippine Center for Investigative Journalism

“yndio arxipelago is a dazzling provocation drawing readers into the intimacies of the first colonial encounters between the Philippines and an emerging Spanish-speaking world…[Merina’s] verses, crisp and riveting, allow us to listen in to historical conversations, experience a scriptworld shifting from the baybayin to Castilian, and share in the internal struggles of a people on the brink of a cultural upheaval.”

—MARLON JAMES SALES, Associate Professor of Spanish, University of the Philippines and Secretary of The Society for Early Transpacific Studies

View and purchase the book via UP Press.

CREDIT: The header image on this page is from the beautiful artwork of José Honorato Lozano, one of his mid-19th Century paintings depicting Ivatan fishermen.

For My Cousins Who Will Choose Who They Are

![]()

FOR MY COUSINS WHO WILL CHOOSE WHO THEY ARE

running home this evening

I look for the san gabriels

to find only

a faint line above the haze

a razor-black definition

of home running

and, before I can help it, my mind

rushes in

fills the rest with detail and reference

so that I see

as if in mid-earthquake

a perfect memory of a mountain.

I tell you this, cousins, because you too

will find your landmarks

this way,

you too will find yourself

listening to others

on the bus in school on t.v.

who will tell you, “You can choose

who you will be

you have the responsibility

to see it this way.”

***

what chose who blood

passages over the dark-rain ocean crossing

the border-blister heat

to arrive

find that address in the suitcase

stolen

***

there is in you

hot blood

cool blood

island blood

lovers blood

tribal blood

white blood

hungry blood

city blood

american blood American blood AMERICAN blood

***

it is twenty-eight day since Grandpa die

we used to eat chilled plums from buckets

drink coke and play ping-pong

in the backyard

one of his countrymen once said,

America

is in the Heart

this after years and years away

from the mountain on the island

***

we will be mis taken

for everything

we will learn to trade the landmarks

for pictures of ourselves

we will be tempted by the temporary ease

of forgetfulness

but, my cousins, after years of pretending

to choose

we will learn: we only know how

to discriminate

you will find yourself

suddenly alone with no easy choices

nothing gets better

once it is gone

or taken

or given

you cannot get it back in one piece

not in one lifetime

so I give you no caution

just a cool eye in the hurricane

just a hot eye in the field

there is something

no one has told you

go to it

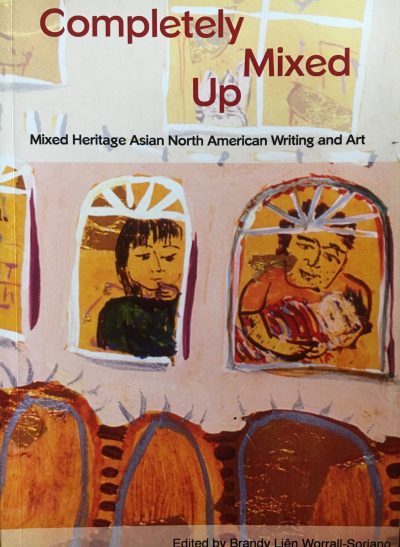

from Completely Mixed Up: Mixed Heritage Asian North American Writing and Art (edited by Brandy Lien Worrall-Soriano, Rabbit Fool Press, 2015)

The Change Giver

![]()

THE CHANGE GIVER

The Change-giver drops four pisos

into my hand

swivels hips sideways

calls out the next stop

Ortigaaaaaaaaaaaaaas

one hand worrying the frayed edge

of a trouser pocket

switching back and forth

coin against the railing

one click means stop

two clicks go

sige dire-diretso hangang sa dulo

The Change-giver paces the small spaces

from Q-mart to Quezon Ave.

feet collecting strips of sun like geckos’ tongues

calling their rattling call in the night

The Change-giver paces the small spaces

between engine-floor to back door

gliding between aisles of torn Salita pages

spit and celphone cards

towel moistens the temple’s soft skin

the clutch gives

rocking wheels

into forward motion

The Change-giver has seen

four-hundred twenty-eight pisos

cross the pockets aisles and fingernails

seen three times already

the slow opening of gates

at city hall

seen the boarding and slipping off

of passengers before dawn

seen the slow crunch of taxis

jeeps and tricycles loosen

into steam-filled streets

moving in one flip

in one toss

the tickets fanned to the blanket of precision

holding in one fist

the day’s slowly burning silence

One-click two-click one-click two

in a flash five centuries of stop and go

five centuries of letting go

five centuries of circling a foreign architect’s dream

of agreement

One-click two-click one-click two

the signals of memory smoking through the sheen

of metal and coin

finger and cloth

One-click two-click one-click two

the stuttering accent of hybrid languages

smoothed to silence

carved from roughness

One-click two-click one-click two

we stop we listen

our tongues

our mouths

our eyes

our hands

the sun clears the billboard on EDSA

fills the window with light

the Change-giver is braced between seats

turning coins into dreams

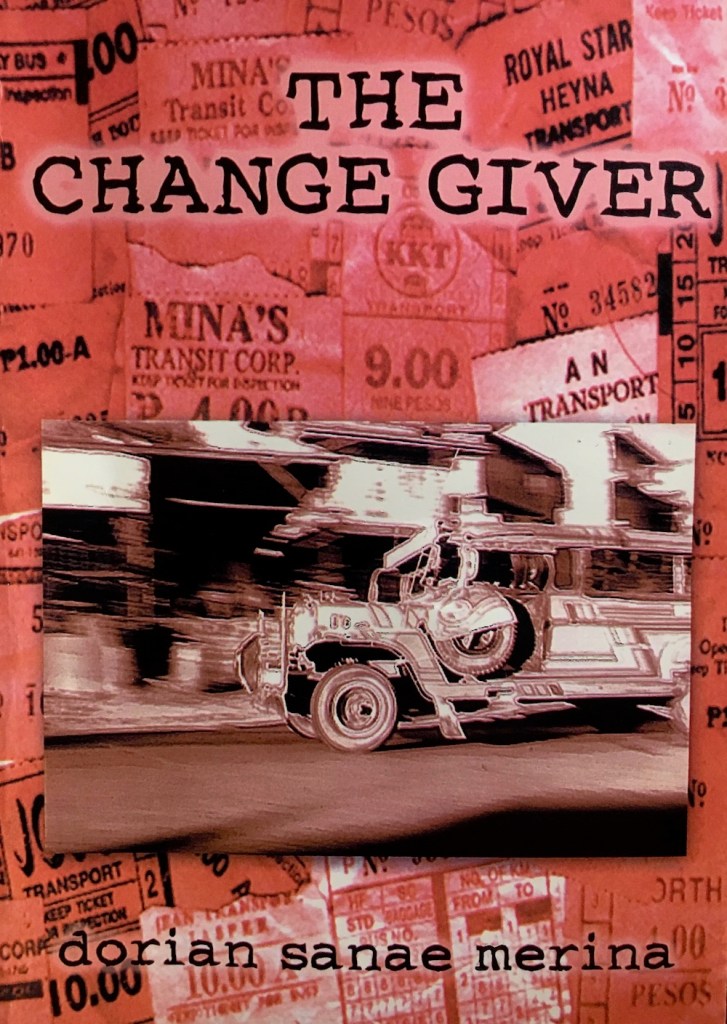

From the chapbook, The Change Giver (Rosela Press, 2003)

Migrations

Collaboration with visual artist Alyssa Sherwood, commissioned by the City of Pasadena. Read the entire poem here at the Poetry Foundation.

Exile

![]()

EXILE

They were exiled

for half a century

from the island

the ocean became

a deep and treacherous

border cut into the land.

The punishment imposed

by Spanish officials

a consequence for insurrection

certain as the fine embroidery

on the priest’s frock ironed hot

and flat for mass.

Even so

some were driven back

by hunger or loneliness

to the green hills

and the damp forests

but always to leave

by nightfall

with dreams of home

fading like salt spray

against the boatsides.

When it was finally over

many did not return

for the passage of time

takes its toll

and heartbreak runs through

generations like

a thirst quenched by water

pulled from the bitter gourd.

The ones who did return

gathered stones and lime

from the shoreline

brought down wood from the hills

and built the homes

where we now live.

This was all more than one hundred eighty years ago

and tonight

look how the first-quarter moon

fills the town streets

with glowing light,

the sky filled with stars

and clouds and wind.

We are still named

for the tree

lodged into the hillsides

its broad leaves turning dark red when

the rainy season nears its end,

inside green teardrops

new leaves wait silently

to open.

Read more about the collection, Di Achichuk.